One may have few social contacts yet not feel lonely, and vice versa. This concept is distinct from the amount of time spent alone 6 or the frequency of social contact 4. In the present study, we focus on the time-enduring, rather than momentary, nature of this negative sense of an unmet social need, which we henceforth refer to as ‘trait loneliness’. A key concern is the experience of ‘loneliness’: the subjective perception of social isolation, or the discrepancy between one’s desired and perceived levels of social connection 4, 5. Consequently, the absence of sufficient social engagement can impose substantial physical and psychological costs. Our species’ extraordinary reliance on other individuals has led to the characterization of humans as the “ultra-social animal” 2. Social interactions are crucial for survival, and fulfillment 3.

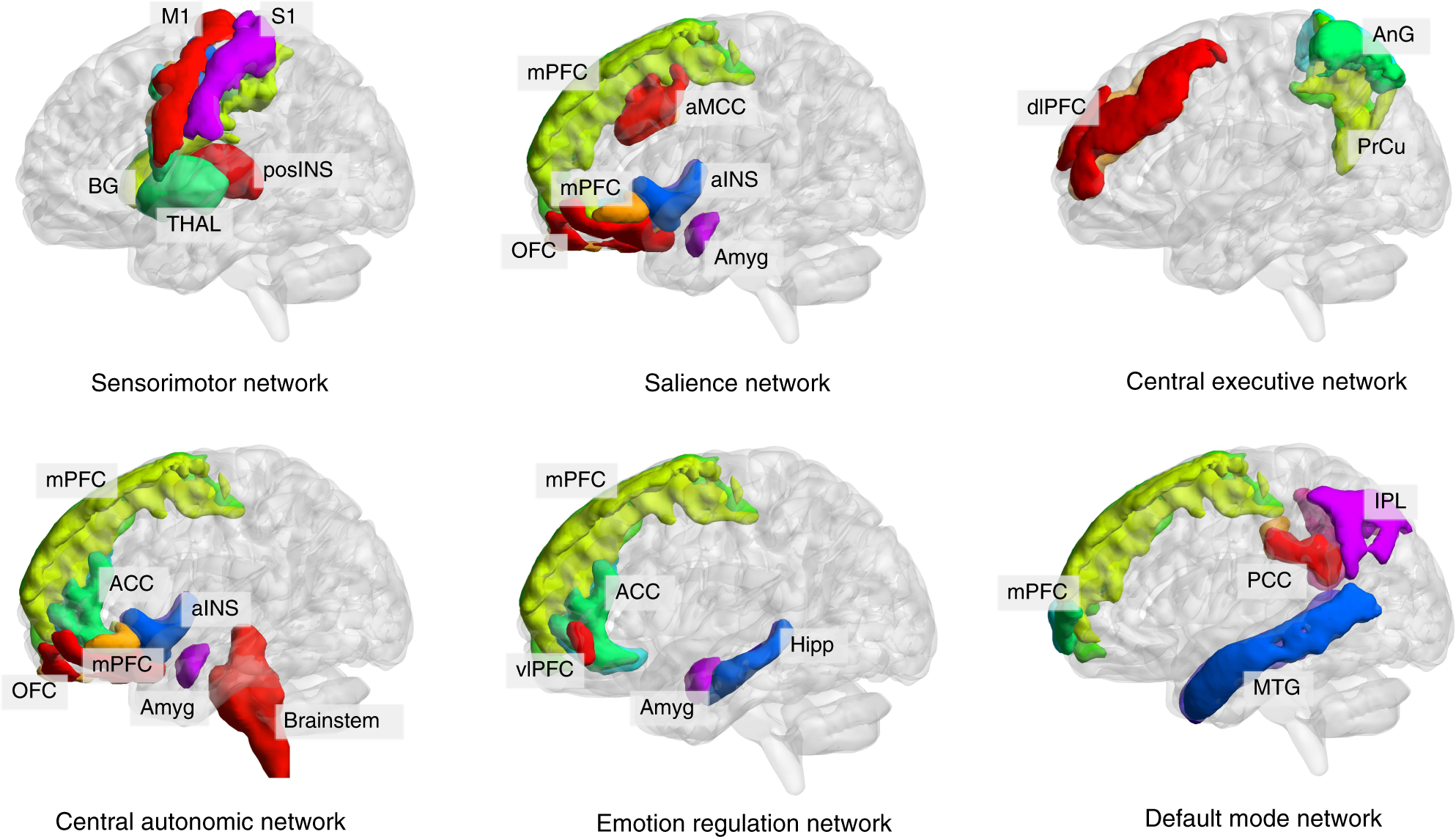

Human evolution has been shaped by selection pressures towards enhanced inter-individual cooperation 1, 2. The findings fit with the possibility that the up-regulation of these neural circuits supports mentalizing, reminiscence and imagination to fill the social void. Lonely individuals display stronger functional communication in the default network, and greater microstructural integrity of its fornix pathway. This higher associative network shows more consistent loneliness associations in grey matter volume than other cortical brain networks. The loneliness-linked neurobiological profiles converge on a collection of brain regions known as the ‘default network’. Using the UK Biobank population imaging-genetics cohort ( n = ~40,000, aged 40–69 years when recruited, mean age = 54.9), we test for signatures of loneliness in grey matter morphology, intrinsic functional coupling, and fiber tract microstructure. Despite severe consequences on behavior and health, the neural basis of loneliness remains elusive. Perceived social isolation, or loneliness, affects physical and mental health, cognitive performance, overall life expectancy, and increases vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias.

Yet, social dependency also comes at a cost. Humans survive and thrive through social exchange.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)